Art Review Portraits in the Grand Style Just a Little Skewed

| John Brewster, Jr. | |

|---|---|

| Built-in | 1766 (1766) Hampton, Connecticut |

| Died | August thirteen, 1854 (1854-08-14) Buxton, Maine |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

John Brewster Jr. (May 30 or May 31, 1766 – August xiii, 1854)[1] was a prolific, Deafened itinerant painter who produced many mannerly portraits of well-off New England families, especially their children. He lived much of the latter half of his life in Buxton, Maine, USA, recording the faces of much of Maine'south aristocracy guild of his fourth dimension.

Co-ordinate to the website of the Fenimore Fine art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, "Brewster was not an artist who incidentally was Deaf but rather a Deafened artist, 1 in a long tradition that owes many of its features and achievements to the fact that Deaf people are, equally scholars accept noted, visual people."[2]

Family and early life [edit]

Brewster's father, Dr. John Brewster Sr., and his stepmother, Ruth Avery Brewster, c. 1795–1800

Little is known near Brewster'south childhood or youth. He was the 3rd child built-in in Hampton, Connecticut, to Dr. John and Mary (Durkee) Brewster. His mother died when he was 17. His father remarried Ruth Avery of Brooklyn, Connecticut, and they went on to take four more children.[3]

John Brewster Sr., a doctor and descendant of William Brewster, the Pilgrim leader, was a member of the Connecticut General Associates and also active in the local church.[4]

One of the younger Brewster'due south "more than touching and polished total-length portraits" is of his male parent and stepmother, according to Ben Genocchio, who wrote a review of an exhibition of Brewster's portraits in the New York Times. They are shown at home in conventional poses and wearing refined but non opulent dress in a modestly furnished room. His mother sits behind her husband, reading while he is writing. "She stares straight at the viewer, though softly, even submissively, while her husband stares off into the distance as if locked in some deep thought."[four]

Existence Deaf from nascence, and growing up in a fourth dimension when no standardized sign language for the Deaf existed, the young Brewster probably interacted with few people outside of the circle of his family and friends, with whom he would have learned to communicate.[iii] A kindly government minister taught him to paint, and by the 1790s he was traveling through Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and eastern New York Land,[2] taking reward of his family connections to offering his services to the wealthy merchant grade.[four]

His younger blood brother, Dr. Regal Brewster, moved to Buxton, Maine in late 1795. The artist either moved up with him or followed soon afterward and painted likenesses in and around Portland in between trips dorsum to Connecticut.[3]

Work as a Deaf artist [edit]

James Prince and Son, William Henry (1801) by John Brewster, Jr. Prince was a wealthy merchant from Newburyport, a aircraft center in Massachusetts. The painter included numerous expensive luxuries to show Prince as wealthy and a gentleman: Curtains and a fine floor indicated wealth; the bookcase with books and the desk-bound suggest learning. The boy is symbolized equally entering globe of adults past his holding a letter. (from the collection of the Historical Society of Old Newbury)

Brewster probably communicated with others using pantomime and a small-scale amount of writing. In this style, Brewster managed the business organisation of arranging poses along with negotiating prices and artistic ideas with his sitters. As an itinerant portraitist working in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in the Usa, he would travel great distances, often staying in unfamiliar places for months at a time.[3]

His Deafness may have given Brewster some advantages in portrait painting, according to the Florence Griswold Museum exhibit web page: "Unable to hear and speak, Brewster focused his energy and ability to capture minute differences in facial expression. He also greatly emphasized the gaze of his sitters, as eye contact was such a critical office of communication among the Deafened. Scientific studies accept proven that since Deafened people rely on visual cues for advice [they] can differentiate subtle differences in facial expressions much better than hearing people."[3]

Influences [edit]

Brewster's early, big portraits bear witness the influence of the work of Ralph Earl (1751–1801), another itinerant painter. Paintings by the 2 artists (especially in Brewster'due south early work) show similar scale, costumes, composition and settings, Paul D'Ambrosio has pointed out in a itemize (2005) for a traveling exhibition of Brewster's work,"A Deafened Artist in Early America: The Worlds of John Brewster Jr."[4]

Earl was influenced by the 18th century English language "Grand Manner" style of painting, with its dramatic, grand, very rhetorical style (exemplified in many portraits by Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Earl and Brewster refashioned the way, changing it from lofty and grand to more humble and coincidental settings.[4]

Career [edit]

In the early on 19th century, Brewster habitually painted half-length portraits which saved him labor, saved his patrons money and "were better suited to his express abilities," according to Genocchio. Some of the paintings are most identical, down to the same clothes and article of furniture, with only the heads setting them apart.[four]

In 1805 his brother, Dr. Imperial Brewster, finished structure of his Federal style house in Buxton, and John Brewster moved in. For the remainder of his life, he lived in the domicile with his brother's family.[three]

Past near 1805, Brewster had his own style of portraying children in total length, with skimpy garments or nightclothes, soft, downy pilus and big, beautiful eyes for a sweet, appealing impact. Simply the perspective issues remained, with the figures seeming out of scale with their environment.[4]

At about this time the creative person also began to sign and date his paintings more frequently. He also moved away from the big-format Grand Style-influenced style and turned to smaller, more intimate portraits in which he focused more attention on the faces of his subjects.[iii]

In the years merely before 1817, Brewster traveled further for clients as his career flourished.[3]

Francis O. Watts with Bird [edit]

Typical of Brewster's portraits is "Francis O. Watts with Bird" (1805), showing "an innocent looking male child with manly features" wearing a nightslip and property a bird on his finger and with a cord. The surrounding landscape is "strangely low and wildly out of calibration—the young boy towers over trees and dwarfs distant mountains. He looks like a behemothic," Genocchio has written.[four] Or he looks as if the viewer must be lying down, looking up at the child from the footing. Brewster always struggled with the human relationship of his figures to the background.[4]

A more than positive view of the portrait comes from the Web folio about the 2006 exhibit at the Florence Griswold Museum website: "Brewster's serene and ethereal portrait of Francis O. Watts is one of his most compelling portraits of a child. In this work—particularly Francis' white dress and the peaceful mural he inhabits—modern viewers oft feel a palpable sense of the silence that was Brewster'southward globe.

"The bird on the string symbolizes mortality because only after the kid's expiry could the bird get free, simply similar the child's soul. Infant mortality was high during Brewster'southward time and artists employed this paradigm often in association with children."[3]

In schoolhouse [edit]

Moses Quinby (c. 1810–1815). Quinby was a successful lawyer from Stroudwater, Maine. He was probably painted when Brewster was traveling in Maine.

From 1817 to 1820, Brewster interrupted his career to learn sign language at the newly opened Connecticut Asylum in Hartford, now known as the American School for the Deaf.[4]

Brewster, at age 51, was by far the oldest in a class of seven students, the average age of which was 19. It was the beginning class that attended the schoolhouse and witnessed the birth of American Sign Language (ASL).[3]

Later life [edit]

When Brewster returned to Buxton and to his portraits, "he seems to take taken more care when painting the faces of his subjects," Genocchio wrote," resulting in portraits that show an increased sensitivity to the characters of his subjects."[4]

Later the 1830s, little is known of Brewster's work—or of Brewster. He died in Buxton on August 13, 1854.

Assessments of Brewster'southward artistry [edit]

Reverend Daniel Marrett (1831). An instance of a Brewster portrait from his late career, many of which evidence great depth and strength of characterization. Marrett's furrowed brow and chisled features convey the seriousness of his convictions. The paper he holds quotes Amos 4:12, "Gear up to come across thy God." (from the collection of Celebrated New England/SPNEA)

Brewster "created hauntingly beautiful images of American life during the determinative period of the nation," according to a page at the Fenimore Fine art Museum website devoted to a 2005–2006 exhibition of the creative person's work.[2] "Working in a style that emphasized simpler settings [than the "Grand Way" style], along with broad, flat areas of color, and soft, expressive facial features, Brewster achieved a directness and intensity of vision rarely equaled."

The Fenimore website also says, "His extant portraits show his ability to produce delicate and sensitive likenesses in full-size or miniature, and in oil on canvas or ivory. He was especially successful in capturing childhood innocence in his signature full-length likenesses of immature children.[ii]

The website says Brewster left "an invaluable tape of his era and a priceless creative legacy."

According to the anonymous writer of the Florence Griswold Museum'south web page about the same exhibit, "Brewster'south Deafness may also take shaped his mature portrait style, which centers on his emphasis on the face of his sitters, especially the gaze. He managed to achieve a penetrating grasp of personality in likenesses that appoint the viewer direct. Brewster combined a muted palette that highlights mankind tones with excellent draftsmanship to draw attending to the eyes of his sitters. The importance of straight eye contact to a Deaf person cannot exist overstated."[iii]

The same author also says, "Brewster was ane of the greatest folk painters in American history as one of the key figures in the Connecticut manner of American Folk Portraiture. In improver, Brewster's paintings serve as a cardinal part of Maine history. Brewster was the most prolific painter of the Maine aristocracy, documenting through the portraits details of the life of Maine's federal elite."

Genocchio, reviewing the exhibit for the New York Times, took a dimmer view, noting Brewster's difficulty with painting backgrounds but admiring his "sweetly appealing" paintings of children.[4]

Some individual works [edit]

Unidentified Woman in a Landscape (c. 1805) (from the drove of the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York)

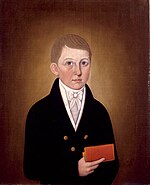

- Boy with Volume (1810); unidentified field of study (Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut, drove)

- Francis O. Watts with Bird (1805) (Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, drove)

- Dr. John Brewster and Ruth Avery Brewster (c. 1795–1800) (Old Sturbridge Village drove)

- Mother with Son (Lucy Knapp Mygatt and Son, George) (1799) (Palmer Museum of Fine art of the Pennsylvania State University collection)

- James Prince and Son, William Henry (1801) (Historical Society of Old Newbury collection)

- Adult female in a Landscape (unidentified subject ) (c. 1805) (Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, collection)

- Moses Quinby (c. 1810–1815) (Bowdoin Higher Museum of Fine art collection)

- Reverend Daniel Marrett, 1831 (Historic New England/SPNEA collection)

- Elizabeth Abigail Wallingford (c.1808) (Brick Store Museum collection)

Exhibits [edit]

- "A Deaf Artist in Early on America: The Worlds of John Brewster Jr.," Fenimore Fine art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, Apr 1 to December 31, 2005; Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut, June 3 through September 10, 2006 (Florence Griswold Museum exhibition sponsored in connection with The American School for the Deafened). The testify, with some augmentation, was at the American Folk Art Museum, New York Metropolis, from October 2006 to Jan 7, 2007.

- The Saco Museum [2] in Saco, Maine, is believed to agree the largest drove of John Brewster, Jr., paintings, including the only known full-length (74 5/eight inches long) developed portraits, Colonel Thomas Cutts and Mrs. Thomas Cutts.

Bibliography [edit]

Comfort Starr Mygatt and His Daughter Lucy, 1799

- [iii] Genocchio, Ben. "Fine art Review: Portraits in the Grand Style, Merely a Little Skewed." New York Times, Sunday, July 29, 2006, "Connecticut and the Region" department, page CT ten, accessed August seven, 2006.

- D'Ambrosio, Paul S. "A Deaf Artist in Early America: The Worlds of John Brewster Jr." Folk Art 31, no. 3 (fall 2006): 38–49.

- Hollander, Stacy C., and Brooke Davis Anderson. American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum. New York: American Folk Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001.

- Lane, Harlan. A Deafened Artist in Early America: The Worlds of John Brewster Jr. Boston: Beacon Printing, 2004.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Kornhauser, Elizabeth Grand. (2011). "Brewster, John, Jr.", The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, vol. i. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 332. ISBN 9780195335798

- ^ a b c d "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-05-24. Retrieved 2006-08-07 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit championship (link) Website of the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, exhibition info folio: "A Deafened Artist in Early America: The Worlds of John Brewster, Jr.," accessed February 28, 2007. - ^ a b c d e f yard h i j k "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-07-17. Retrieved 2006-08-07 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Website of the Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut, exhibition info folio: "A Deaf Artist in Early on America: The Worlds of John Brewster Jr.," accessed February 28, 2007 - ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j one thousand l [1]"Fine art Review: Portraits in the Grand Style, Simply a Picayune Skewed," by Benjamin Genocchio, New York Times, Sun, July 29, 2006, "Connecticut and the Region" department, folio CT 10, accessed Baronial 7, 2006

External links [edit]

- Fenimore Art Museum official website

- Florence Griswold Museum official website

- American Folk Fine art Museum official website

- sound and video versions of a 2004 lecture by Brewster biographer Harlan Lane The lecture is sign language interpreted.

- Marriage Listing of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Total Record Brandish for John Brewster. Getty Vocabulary Plan, Getty Inquiry Plant. Los Angeles, California.

- "John Brewster Jr.: An Artist for the Needleworker" by Davida Tenenbaum Deutsch in The Clarion, Autumn 1990.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brewster_Jr.

0 Response to "Art Review Portraits in the Grand Style Just a Little Skewed"

Post a Comment